Wrong Impression

“We don’t reveal this definition externally”

Introduction

On in the early afternoon, I was at my desk in the New York City engineering office of Meta née Facebook and checking the status of my advertising campaigns. (Since I focus on events that largely predate the rebranding, I’ll stick with Facebook.) As an advertising company, Facebook encourages its employees to conduct their own advertising campaigns and supports those efforts with monthly advertising credits. I had been using those credits to boost posts on Instagram, while also experimenting with the composition of target audiences. Since advertising metrics still felt somewhat alien to me despite more than six months at the firm, I decided to look up basic metrics, notably ad impressions, on the firm’s wiki. I was about to discover compelling evidence that Facebook was artificially inflating that very metric and thereby misleading paying customers, investors, and regulators alike.

First Impressions

Before we get to what I found, let’s make sure we understand what ad impressions are and what role they play in Facebook’s business. To get started, we turn to the Facebook Business Suite. The smartphone app is an indispensable tool for creating and monitoring ads on Facebook. In , the app’s builtin help defined ad impressions thusly:

The number of times your ads were on screen

In other words, an impression happens only when an ad is displayed on screen. That makes sense. But it also leaves unspecified who, if anyone, looks at that screen. Let’s dig a little deeper. Since Facebook is a publicly traded company, it must make regular filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission or SEC. Those filings matter because they help investors and regulators understand a company’s business as well as evaluate its future prospects.

The quarterly and yearly reports covering the day I made my discovery are Form 10-Q as filed with the SEC on and Form 10-K as filed on . Both filings contain a section titled Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations and a subheading Components of Results of Operations — Revenue. That’s where the firm’s management, foremost CEO Mark Zuckerberg, spell out how they understand the business they are in and how that business generates its revenue. The first two paragraphs, labelled Advertising, are identical in both filings and read (emphasis mine):

We generate substantially all of our revenue from advertising. Our advertising revenue is generated by displaying ad products on Facebook, Instagram, Messenger, and third-party affiliated websites or mobile applications. Marketers pay for ad products either directly or through their relationships with advertising agencies or resellers, based on the number of impressions delivered or the number of actions, such as clicks, taken by users.

We recognize revenue from the display of impression-based ads in the contracted period in which the impressions are delivered. Impressions are considered delivered when an ad is displayed to a user. We recognize revenue from the delivery of action-based ads in the period in which a user takes the action the marketer contracted for. The number of ads we show is subject to methodological changes as we continue to evolve our ads business and the structure of our ads products. We calculate price per ad as total ad revenue divided by the number of ads delivered, representing the effective price paid per impression by a marketer regardless of their desired objective such as impression or action. For advertising revenue arrangements where we are not the principal, we recognize revenue on a net basis.

In short: Facebook generates almost all revenue through advertising, which maximizes either impressions or actions. Impressions requires display of the ad to human users. Impressions also are the more fundamental metric, with price per impression reported for all ads.

Two years later, the firm’s most recent Form 10-K, filed with the SEC on , includes a whittled down first paragraph only but the three points still are the substance of Facebook’s explanation for its revenue.

Actual Impressions

Alas, Facebook’s actual, technical definition for ad impressions is substantially different:

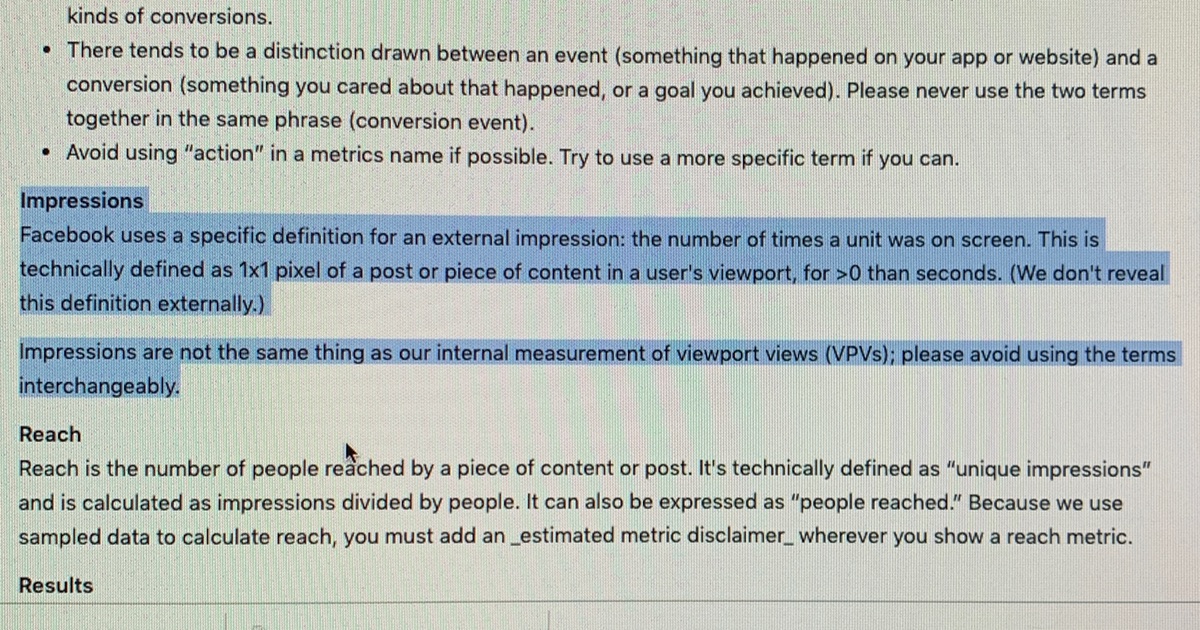

Facebook uses a specific definition for an external impression: the number of times a unit was on screen. This is technically defined as 1x1 pixel of a post or piece of content in a user’s viewport, for >0 than seconds. (We don’t reveal this definition externally.)

This definition remains Facebook’s actual definition for ad impressions to this day. The only thing that has changed is that Facebook started sharing that definition with the outside world in . That page has an embedded view counter, but with today’s count at 928 smaller than the 1,381 on my last visit on , I have some reservations about the counter’s accuracy. Still, that page does not seem particularly popular or easy to find. I couldn’t. Experienced staff at the New York Times did.

By comparison, the Media Rating Council (MRC), an industry-funded, self-regulatory organization, states in its Viewable Ad Impression Measurement Guidelines for mobile as well as desktop that its viewable ad impressions require showing at least 50% of the ad’s pixels for at least 1s. It also requires that the ad delivery system tracks non-viewable as well as undetermined ad impressions in addition to viewable ones and that all three be disclosed to advertisers.

That same organization has also accredited Facebook for its handling of ad impressions in the newsfeeds of the Facebook and Instagram social networks. However, the accreditation only covers its minimum standards, which do not specify any quantitative thresholds.

Analytical Impressions

Facebook’s technical definition of ad impressions comprises only 50 words. But when you consider context and implications, they have tremendous impact. Let’s explore just that impact.

- There is no plausible technical reason that might justify this definition. Determining the visible rectangle of some view element is straight-forward for applications running on the iOS and Android operating systems. It used to be slightly more complicated for web browsers. But that has become straight-forward too.

- This definition gives Facebook tremendous latitude in delivering ad impressions. In the worst case for advertisers, Facebook claims that it delivered some number n of ad impressions, when in manifest reality it delivered only n corner pixels. Then again, maybe the firm did deliver n complete ad impressions. The technical definition renders ad impressions useless to advertisers.

- At the same time, the one-square-pixel threshold for ad impressions is exceedingly useful to Facebook. The firm invariably records more ad impressions because not all ads need to be fully visible in order to qualify. But that is only the baseline, best-case scenario. If Facebook decided to exploit that definition, it has tremendous opportunities for artificially inflating ad impressions even further.

- Taken together, the first three analytical impressions point towards economic self-interest as primary motivating force, even if that includes cheating on its paying customers. The definition’s parenthetical only strengthens that interpretation. Why else add such suggestive language? Worse, the very presence of the parenthetical on a widely accessible wiki page points to a firm culture largely unencumbered by ethics or even scruples.

- Facebook has definitely exploited this definition — to a degree that (some) advertisers noticed. I am confident of that because of a conversation with another software engineer, who used to work on Google’s ad team. When I told the story of the one-square-pixel threshold, the engineer seemed unimpressed, responding: “We long suspected that!” Apparently, some Facebook customers could not make sense of reported numbers and took their complaints to the competition.

- Yet in conversations with journalists and lawyers about the technical definition, I received feedback that (unnamed, presumably institutional) advertisers were also unimpressed. That puzzled me for the longest time — until I started looking into ad verification. After a Wall Street Journal article about Facebook miscalculating a key video metric for two years, Facebook reviewed its own metrics collection and found several more metrics that were faulty too. To reassure the advertising industry, the firm agreed to an MRC audit and installed data taps for third-party ratings firms. The implication now is obvious: Institutional advertisers aren’t particularly concerned about Facebook (possibly) cooking the books because they have their own, independent books.

- That still leaves one sizeable group of advertisers who remain fully exposed to Facebook’s mostly arbitrary ad impressions: individuals and small businesses. They do not have the resources to pay for third-party verified metrics. They most likely do not even have the awareness that anything might be amiss. After all, Facebook doesn’t exactly highlight the technical definition and continues peddling its fantasy of meaningful ad impressions in advertising platform and regulatory filings. Given that context, Facebook using “Speaking Up for Small Businesses” as the public relations angle in a recent fight with Apple, which has Facebook opposing a move by Apple that meaningfully improves privacy, truly strains credulity.

- Facebook subjecting itself to an outside audit and providing ratings firms with direct data taps in early was unexpected. After all, this is the same firm that last year fought academic researchers and journalists monitoring political advertising on Facebook by disabling their tools as well as by deplatforming the auditors — despite or more likely because of the intense public interest in that work. Upon reflection, however, the opposite reactions are perfectly consistent with a single imperative: to protect the thin patina of legitimacy that remains of the firm’s reputation and, more importantly, its economic self-interest at all costs.

Personal Impressions

So what are we to make of all this?

To me personally, the most infuriating aspect of discovering the technical definition was the parenthetical. I would read the technical definition two years later and reliably, immediately feel an immense anger building up inside. That co-opting “we” of the ethically compromised who don’t share externally was truly triggering because deeply insulting. With some more distance, I can attest that the technical definition and its parenthetical are incredibly sleazy indeed. But in motivating me to leave Facebook again, it also served a positive function. Three months later I declared: “So long, and thanks for all the gelato!” That’s the only positive thing about my nine months with the firm.

Facebook’s handling of ad impressions is yet another instance where the firm seeks advantage for itself with no regard whatsoever for the consequences on others. But it doesn’t stop there. If it wasn’t for third-party ratings firms, the technical definition would render the most foundational metric of its advertising platform meaningless. That’s how far Facebook will go for extracting more and more profits, to turn even its own business into one ginormous scam — and to do so despite the fact that the legitimate version of its micro-targeting ad delivery system produces astounding profits already.

That institutional advertisers didn’t want to get involved in a quarrel that doesn’t impact them directly seems reasonable only for a moment. But then the naked self-interest becomes readily apparent because institutional advertisers can’t trust Facebook either. It’s just that the current arrangement meets their needs and they don’t want to upset the status quo. As it turns out, the sleazy reputation of the advertising industry really is earned. In that, Facebook and its largest customers are made from the same tempting but cheaply spun cloth that might just rip at any moment or leave a chemical burn on your skin. They do deserve each other.

Finally, we can, with some confidence, point towards the one force that eventually will consume Facebook whole: Facebook itself. We got a first taste of just that eventuality in recent weeks, when Zuckerberg’s obsession with the metaverse turned into plans to spend $10 billion just this year and no end to the unhinged spending in sight thereafter. That hubris rightly spooked investors, triggering a major stock sell-off on that knocked a record-setting $232 billion off Facebook’s market value just that day. The stock has lost another 13% of its remaining value or $86 billion since then.

I would lie if I claimed that I didn’t feel some Schadenfreude at this turn of events. But the thing is, if I was Mark Zuckerberg, I’d probably try to build the metaverse as well. Because when I look at the totality of his record and the ghosts of the many who died in Myanmar and in Ethiopia stare accusingly back, I too would want to escape myself into the metaverse!